How to clone a GitHub repository

These days it’s essential to know how to clone a GitHub repository as GitHub is the de-facto standard for source code repositories. According to this source, GitHub has 100 million users. If you follow tech blogs, such as this one, you will be asked to clone a GitHub repository to follow along. In this post, you will look into all the ways to download code from GitHub to quickly get the source code you need without setting it up on the spot.

You can pick any public repository on GitHub to follow along. In this example, I will choose one from trending repositories: Awesome Security Hardening.

Method 1: Download Zip File

If you don’t have anything on your computer, the easiest way to get the latest code from a GitHub repository is the Download Zip option.

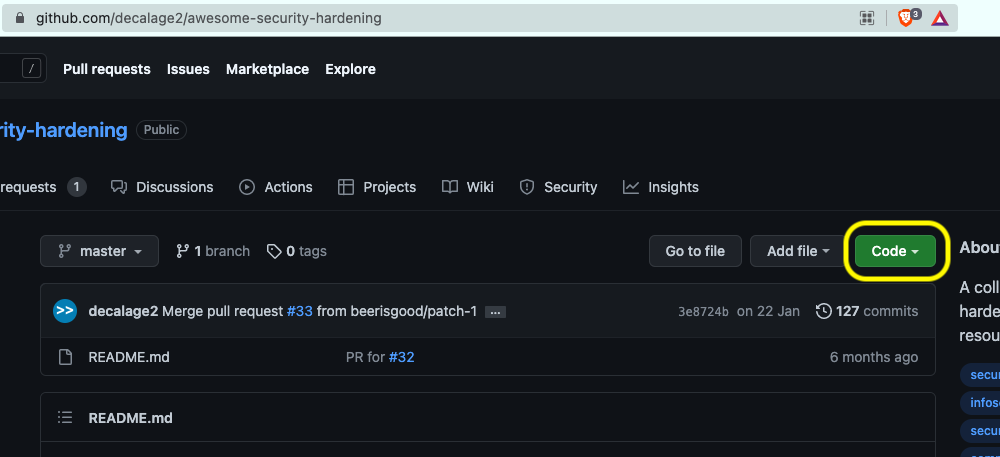

When you land on the repository page, you will see a green button that says Code in the middle:

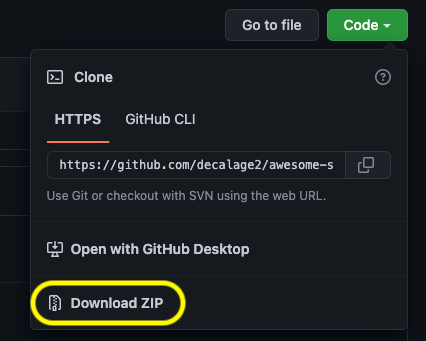

Click the Code button and click the Download ZIP button in the dialog:

Your download should start automatically.

This method works even if you’re not logged in to GitHub.

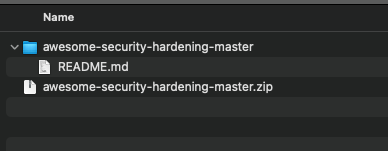

Locate the downloaded file and extract:

This example contains a single README.md file, as shown in the screenshot above.

Method 2: HTTPS

You need to have Git CLI installed on your computer for this method.

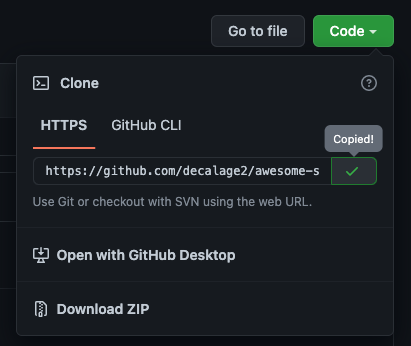

Click the Code button and copy the link shown in the HTTPS tab:

In a terminal, navigate to the parent folder where you want to save the source code and run the following command:

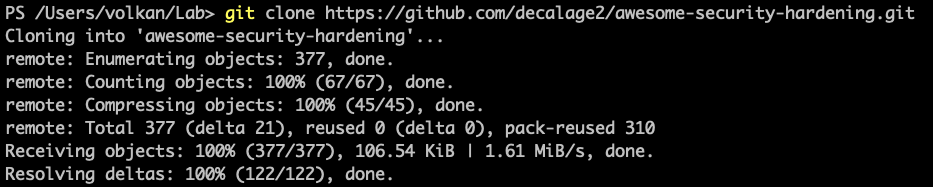

git clone https://github.com/decalage2/awesome-security-hardening.git

You should see the results that look like this:

Method 3: SSH

You need to have Git CLI installed on your computer for this method. Also, you have to be logged in to your GitHub account and have created and set up an SSH key. See the GitHub support page to set up an SSH key.

As you may have noticed in the screenshots of Method 1 and Method 2, the SSH method is not visible when you are not logged in to your GitHub account.

First, log in to your account for the SSH method to work.

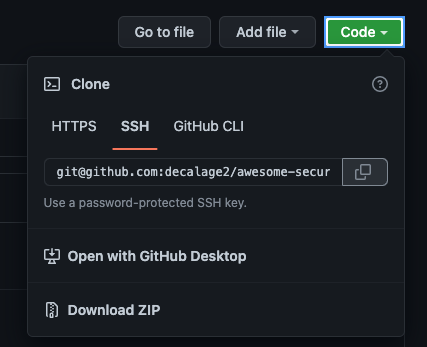

Then, visit the URL of the repository and click the Code button and copy the SSH link:

In the terminal, run the following code:

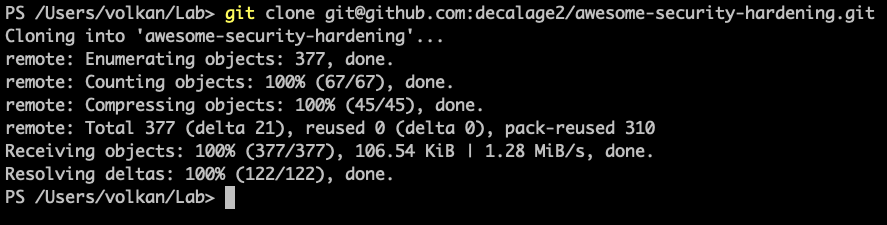

git clone git@github.com:decalage2/awesome-security-hardening.git

The output should look like this:

Method 4: GitHub CLI

If you are using GitHub frequently, I’d recommend installing GitHub CLI.

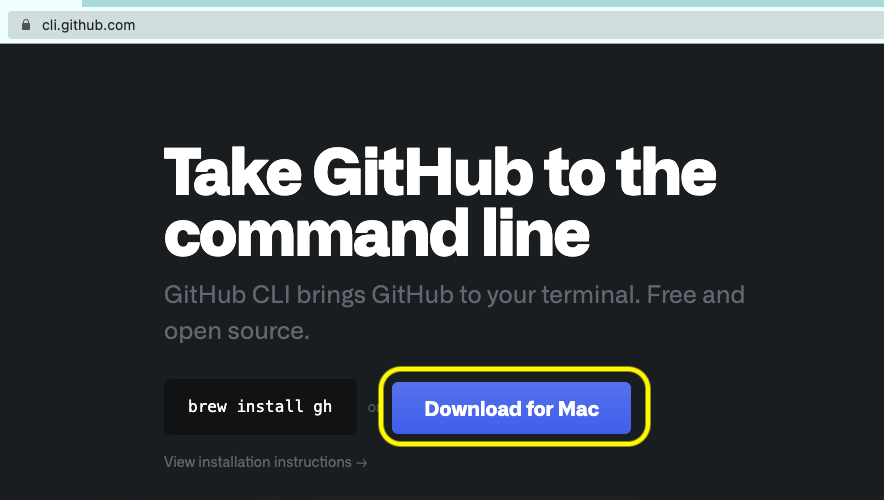

Visit cli.github.com and click the Download button on the screen:

If you use Windows or Linux, GitHub will automatically show you the relevant download link.

If you are using macOS, I’d recommend using brew to install. Brew is a package manager for macOS and Linux, and you can install it by going to brew.sh and running the installation script.

Then you can install GitHub CLI by simply running the following code in your terminal:

brew install gh

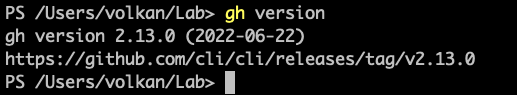

After you’ve installed the CLI, run the following command to confirm it’s installed successfully:

gh version

You should see something like this:

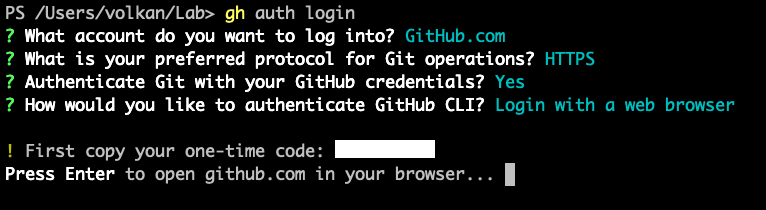

Once you have the CLI installed, you have to log in to your GitHub by running

gh auth login

Select the options that match your environment and circumstances using the interactive CLI. For example, in the example below, I selected GitHub.com, HTTPS and Yes to log in with GitHub credentials and selected Login with a web browser:

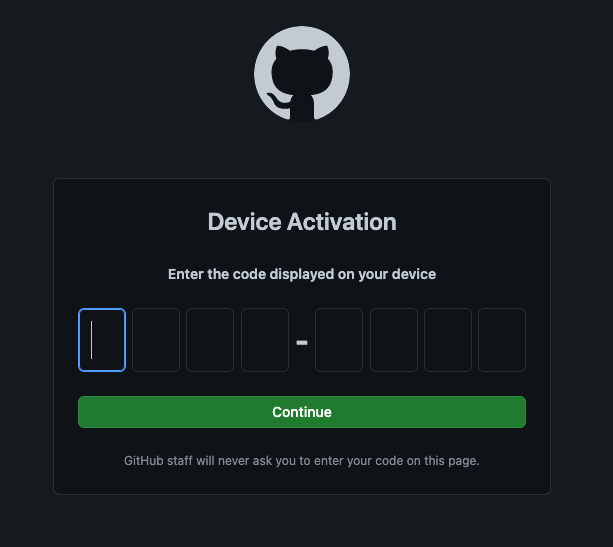

Then, open GitHub.com in your default browser and enter the one-time code displayed on your terminal.

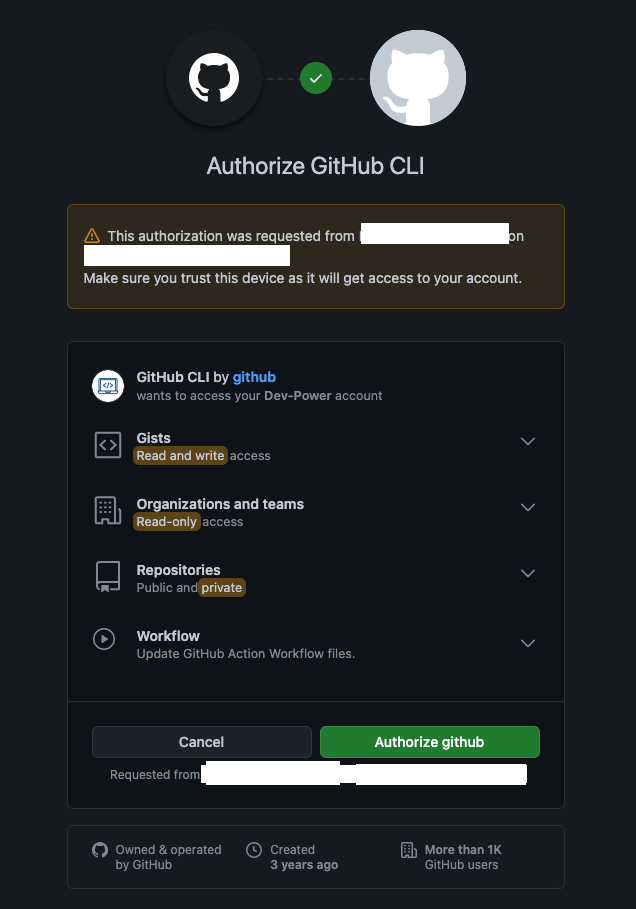

Then accept the authorization request for the CLI to access your GitHub account:

After the CLI has been installed and authorized, cloning a GitHub repository is very easy. Run the following command to clone the example repository:

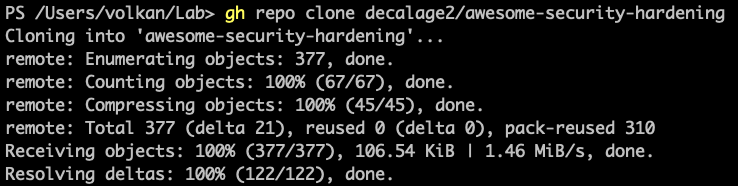

gh repo clone decalage2/awesome-security-hardening

and you should see the successful results:

Conclusion

You walked through all four methods to clone a GitHub repository in this article. Having the ability to clone a repository on GitHub is very important for a developer. So I hope you enjoyed this article and spent some time setting up your environment to be a more productive developer.